Musicians as athletes

I affirm this with the conviction of someone who knows these two universes well: musicians are high-performance athletes, but they do not treat themselves as such. Professional musical performance and high-performance sports require very similar levels of commitment, as well as physical and mental demands. The time, commitment and consistency required to achieve a high level of performance playing an instrument or performing a specific sport skill have much more in common than one might initially think. Some differences will lie in the fact that, in general, neuromuscular recruitment associated with playing an instrument has a greater focus on fine motor skills (i.e. short movements of greater precision and performed mainly with the limbs extremities) and less at the level of gross motor skills (i.e. larger movements involving larger muscle groups) that we normally associate with sports movements. However, it should be clarified that both large muscle groups play an important role, particularly at a postural level, in instrumental performance, and the smaller muscles associated with fine motor skills also play a fundamental role in most sports movements.

For example, if we establish a parallel between playing the violin and performing a given sport specific skill in tennis, we find that, although at different levels, a balance of fine and gross motor control is necessary for better performance in both activities. When we play the violin, we want to maintain a high and controlled posture so that holding the violin with the non-dominant arm and handling the bow with the dominant arm allows the fine work of the hands and fingers to occur as efficiently as possible. Now, if the musculature involved in the stabilization of the trunk and in the elevation of the arms is weak, fatigue sets in more quickly resulting in postural loss, in an execution carried out with greater muscle tension and consequently in a worse performance. In the case of the serve in tennis, due to the high demand for motor coordination and strength involving all the large muscle groups of the lower and upper body, there is also a need for high levels of fine motor skills coordination regarding wrist, hand and finger movements, in order to implement a given spin effect and the desired direction to the ball.

In fact, both musical and sports performance involve neuromuscular recruitment to produce movement and work that requires precision, speed, endurance and strength. In addition, and particularly at a professional level, playing an instrument and playing a sport are activities that require long hours of repetitive movements that, combined with poor physical conditioning, can lead to a variety of clinical conditions. It is unthinkable that a highly competitive athlete does not follow a training program targeting the development of his/her physical qualities which should be complementary to the practice of his/her sport. It is easy to recognize that a good physical fitness level will ensure greater resilience and longevity in sports. The same applies to musical performance. Musicians are high-performance athletes and should prepare themselves as such! Living and playing with pain is not inevitable, it is an option.

The prevalence of pain and injury in musicians

As the years go by and the hours playing their instrument accumulate, it is almost inevitable that professional musicians develop musculoskeletal and/or neuromuscular problems of varying severity at some point in their career. More so if they do nothing about their physical preparation. Review studies on the prevalence of injuries in professional musicians point out that 76% of musicians suffer or have suffered from physical problems that prevent them from performing at their usual level and 84% had injuries that interfered negatively with their musical practice1. Some musicians will develop tendinopathies and low back pain of varying intensity, which they will be able to manage with chronic intake of anti-inflammatory medications or simply by playing less frequently and/or just by enduring pain and discomfort. Others will develop more serious overuse injury syndromes that will become chronic and compromise not only quality of musical performance, but also quality of life, forcing them to periods of musical inactivity. Additionally, others will suffer from even more serious forms of injury that may result in abandoning their career as an instrumentalist musician.

In general, the most frequent injuries affecting musicians manifest themselves through pain and/or dysfunction, especially on the joints, tendons, ligaments and nerves of the upper limb, head, neck and spine. For example, in orchestral instrumentalists, injuries of musculoskeletal and/or neuromuscular origin are more common and affect about 64% musicians, of which 20% consist of peripheral nervous problems and about 8% of cases of focal dystonia2. It makes sense, considering that these are the most stressed areas of the body during instrumental practice. An exception would be the cases of focal dystonia, which, although it may be accompanied by pain and musculoskeletal injury, the root cause of the dysfunction observed at the peripheral level is actually central, that is, the dysfunctional neuronal circuits are at the upper levels of the central nervous system such as the cerebral cortex. Thus, the most frequent injuries in instrumentalist musicians can be summarized as follows3:

- Musculoskeletal injuries – epicondylitis, tendinopathies (tendinosis, tendinitis, tenosynovitis), bursitis, arthritis, arthrosis, osteoarthritis, contractures, injuries to the temporomandibular joint;

- Nerve trapping and inflammation – carpal tunnel syndrome, thoracic outlet syndrome, radial tunnel syndrome, ulnar nerve compression syndrome, ulnar tunnel syndrome, cervical and lumbar radiculopathies;

- Hypermobility;

- Focal dystonia;

- Hearing loss.

The onset of injuries in musicians is due to an array of factors that naturally interact. Several authors have identified the following factors facilitating and/or causing the development of injuries in musicians1:

- Physiological and biological factors such as gender and age. Women seem to be more likely to develop peripheral musculoskeletal and nerve injuries compared to men, and individuals who engage in high volume instrumental practice at an early age, at 4-5 years of age, are also more likely to develop injuries later in life4,5. In the case of focal dystonia, there is a clear higher prevalence in males (over 90%) and in women with menstrual disorders, which suggests that hormonal factors may be predisposing to the development of this disorder6.

- Type of instrument. The characteristics of the instrument (size, shape and weight) and the time of practice imply different levels of physical demand, in which fatigue onset and an execution based on too much physical effort can lead to the development of injuries7. For example, the position needed to play the clarinet implies that the entire weight of the instrument is supported on the right thumb, and at the same time it requires a large amount of short and fast movements of the fingers of both hands8. Another example particularly special to me is the double bass. A bulky instrument with an air column of considerable inertia, which requires not only considerable grip strength to press on the strings, but also considerable whole body physical effort (which, can of course, be optimized with efficient technique) to move this column of air and make the instrument vibrate and produce sound. Anyone who has tried playing the double bass for a few minutes realizes the physical demands that playing this instrument encompasses.

- Instrumental technique. A poor instrumental technique, with non-optimized positions, based on physical effort rather than on movement efficiency, associated with long hours of practice without rest, will naturally predispose the player to pain and injury, especially in the wrists, hands, neck and shoulders9 .

- Specific technical demands. The technical demands of a particular musical piece that often requires high-speed and high-intensity execution, with fatiguing repetition of movements or maintenance of extreme hand positions for a long period of time. All of this creates high levels of mechanical stress and may cause injury10,11.

- Body asymmetry. In the same way that an athlete of a one-side dominant sport will try to compensate for these asymmetries by working out both sides of the body, a musician is in a similar situation, because playing an instrument implies asymmetrical work in very unnatural positions for long periods of time, which will favor the occurrence of various muscular imbalances12.

- Poor physical fitness. Good levels of strength and general physical conditioning are essential to maintain a good position to play an instrument for long periods of time. Most of these positions are very unnatural. Being in good physical fitness will allow to resist the onset of fatigue, recover more quickly between rehearsals or practice sessions, and in fact, it will allow to tolerate more hours of practice avoiding technique and performance deterioration7. Muscle imbalances and weakness resulting from long hours of sitting in certain positions and high volume repetition of short movements must be prevented through exercise programs aiming to strengthen the body globally, and at the same time to compensate for muscle imbalances induced by instrumental practice13.

- Other lifestyle factors. We know that lifestyle factors such as smoking or smoke exposure, alcohol consumption, sleep deprivation, malnutrition, poor hydration and obesity have very damaging effects at a systemic level on our body. Regarding neuromuscular injuries, we know that all these forms of toxicity weaken the body’s connective tissue (cartilage, tendons, ligaments, membranes), muscles and nerve conduction, predisposing to the development of localized inflammatory processes as well as chronic injuries. For example, did you know that obesity is highly predisposing to development of carpal tunnel syndrome?14 Or that smoking is strongly associated with development of injuries and dysfunctions in the shoulder?15

Preventing and resolving injuries in musicians

Any elite athlete empirically knows something that has long been supported by science. That the most effective way to prevent (and also treat) overuse or overload injuries due to high volume sports practice is to ensure good levels of physical fitness combined with good recovery habits, adequate rest and nutrition. Regarding physical fitness, it is unthinkable for an elite athlete, not to follow a regular physical training program. An athlete knows that this will have negative consequences both on sports performance and on the susceptibility for developing injuries. The athlete knows that the weaker his/her musculoskeletal system is, the greater the vulnerability to injury. The question is, and if we consider that professional musicians are required to engage on activities requiring high physical and mental performance for long hours of daily practice, shouldn’t musicians treat themselves as high-performance athletes? I am certain that they should.

In fact, a 2019 systematic review investigating the topic of physical training for professional orchestra musicians1 indicates that following a structured physical training program of varying durations (from a few weeks to several months) has generally resulted in significant improvements in musical performance and in reducing (and even eliminating) chronic pain1.

To keep playing at the highest level for a long time, musicians would greatly benefit if they treated themselves as high-performance athletes and ensure that they maintain good physical shape combined with good habits of recovery, rest and nutrition. And to be clear, when I talk about staying in good physical shape, I don’t mean playing sports. In fact, playing sports as a mean to improve one’s physical fitness is not ideal and can even be harmful. More activity with asymmetric characteristics would be added on top of another, also asymmetric, which is playing a musical instrument. In general, all sports are constituted by specialized movements, and for that reason, also asymmetrical. So, except for purely recreational reasons (which can also be positive at a mental and stress release level), the practice of a sport as a strategy to improve physical fitness is not ideal and should not be the first choice particularly by musicians (I discuss this very topic in this article: Why musicians should not play sports).

General physical fitness is improved through the process of training our physical qualities. This should entail an assessment of the initial status in order to identify specific limitations and outline a specific intervention strategy. One should always start at the base and progress from there, just like the process of learning to play a musical instrument. Here, attention to detail is key. A well-designed training program implies the management of training variables specific to the profile and objectives of the athlete or, in this case, the musician. A correct selection of exercises is crucial, as well as close monitoring of their implementation regarding form of execution, training load and progression over time. As I mentioned, it is not very different from the process of learning to play a musical instrument!

For a musician, playing the instrument is the top priority. It can be obsessive, I know. But playing better in the long run does not necessarily mean playing more hours, but rather investing in taking care of the ‘’machine’’ that is our body. I reiterate once more that playing with pain or discomfort is an option and not an inevitability. Take care of your body and treat it well, because you will need it in the long run!

Train well to play well!

Nuno Correia

References:

- Gallego, C., Ros, C., Ruíz, L., Martín, J. (2019). The physical training for musicians. Systematic review. Sportis Sci J, 5 (3), 532-561.

- Lederman, R. J. (2003). Neuromuscular and musculoskeletal problems in instrumental musicians. Muscle & Nerve, 27(5), 549–561.

- Betancor Almeida, I. (2011). Hábitos de actividad física en músicos de orquestas sinfónicas profesionales: un análisis empírico de ámbito internaciona Tesis Doctoral. Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria.

- Fishbein, M., Middlestadt, S., Ottati, V., Straus, S., y Ellis, A. (1988). Medical problems among ICSOM musicians: Overview of a national survey. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 3(1), 1–8.

- Viaño, J. J. (2004). Estudio de la relación entre la apariciación de lesiones musculoesqueléticas en músicos instrumentistas y hábitos de actividad física y vida diaria. En III Congreso De La Asociación Española de Ciencias Del Deporte. Valencia: Universidad de A Coruña.

- Rosset-Llobet, J., Candia, V., Fàbregas, S., Ray, W., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2007). Secondary motor disturbances in 101 patients with musician’s dystonia. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry, 78(9), 949–953.

- Sardá, E. (2003). En forma: ejercicios para músicos. Barcelona: Paidos.

- Thrasher, M., y Chesky, K. (1998). Medical problems of clarinetists: Results from the U.N.T. musician health survey. The Clarinet, 25(4), 24–27.

- Wynn, C. B. (2004). Managing the physical demands of musical performance. En Williamon A. (Ed.), Musical excellence: Strategies and techniques to enhance performance (pp. 41–60). Londres: Oxford University Press.

- Bejjani, F. J., Kaye, G. M., y Benham, M. (1996). Musculoskeletal and neuromuscular conditions of instrumental musicians. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 77(4), 406–413.

- Mark, T., Gary, R., y Miles, T. (2003). What every pianist needs to know about the body: a manual for players of keyboard instruments: piano, organ, digital keyboard, harpsichord, clavichord. GIA Publications. Martín.

- Ackermann, B., Adams, R., y Marshall, E. (2002). Strength of endurance training for undergraduate music majors at a university? Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 17(1), 33– 41.

- Frabretti, C., y Gomide, M. F. (2010). A saúde dos músicos: dor na prática profissional de músicos de orquestra no ABCD paulista. Revista Brasileira de Saúde Ocupacional, 35(121), 33– 40.

- Shiri R, Pourmemari MH, Falah-Hassani K, Viikari-Juntura E. The effect of excess body mass on the risk of carpal tunnel syndrome: a meta-analysis of 58 studies. Obes Rev. 2015;16(12):1094-1104.

- Bishop, Julie Y. et al. (2015). Smoking Predisposes to Rotator Cuff Pathology and Shoulder Dysfunction: A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy, Volume 31, Issue 8, 1598 – 1605.

Os músicos como atletas

Afirmo-o com a convicção de quem conhece bem estes dois universos: os músicos são atletas de alto rendimento, mas não se tratam como tal. A performance musical profissional e a performance desportiva de alto rendimento obrigam a níveis de compromisso e exigência física e mental muito semelhantes. O tempo, empenho e consistência necessários para alcançar uma performance de alto nível a tocar um instrumento ou no desempenho de um desporto específico têm muito mais em comum do que se poderia, à partida, pensar. Algumas diferenças residirão no facto de, duma forma geral, o recrutamento neuromuscular associado a tocar um instrumento ter um enfoque maior ao nível da motricidade fina (i.e. movimentos curtos de maior precisão e executados iminentemente com as extremidades) e menor ao nível da motricidade grossa (i.e. movimentos de maior amplitude envolvendo os grupos musculares de maior dimensão) que normalmente identificamos associados aos gestos desportivos. Contudo, convém esclarecer que tanto os grandes grupos musculares, como os músculos de menor dimensão associados à motricidade fina, têm uma função importante a nível postural, na execução instrumental e nos mais variados gestos desportivos.

Por exemplo, se estabelecermos um paralelismo entre tocar violino e a execução de um gesto desportivo como o serviço no ténis, verificamos que, embora a diferentes níveis de exigência, um equilíbrio do controlo motor fino e grosso é necessário para uma melhor performance em ambas as actividades. Quando tocamos violino, queremos manter uma postura alta e controlada por forma que o segurar do violino com o braço não dominante e o manejar do arco com o braço dominante, permita que o trabalho fino das mãos e dedos ocorra da forma mais eficiente possível. Ora, se a musculatura envolvida na estabilização do tronco e na elevação dos braços for fraca, a fadiga instala-se mais rapidamente resultando numa deterioração postural, numa execução em maior esforço e consequente numa pior performance. No caso do serviço do ténis, à elevada exigência de coordenação motora e força envolvendo todos os grandes grupos musculares do membro inferior e superior, junta-se a necessidade de coordenação fina ao nível dos movimentos do pulso, mão e dedos, por forma a imprimir na bola o efeito e a direcção que se pretende.

De facto, tanto a performance musical como a desportiva envolvem recrutamento neuromuscular para produzir movimento e trabalho que requer precisão, velocidade, endurance e força. Além disso, e sobretudo a um nível profissional, tocar um instrumento e praticar um desporto são actividades que obrigam a longas horas de prática de gestos repetitivos que, aliado a um mau condicionamento físico, poderá conduzir a uma variedade de problemas médicos. É impensável que um atleta de alta competição não siga um programa de treino das qualidades físicas complementar à prática do seu desporto. É fácil de entender que é uma boa condição física de base que irá garantir maior resiliência e longevidade na prática desportiva. O mesmo se aplica à performance musical. Os músicos são atletas de alta competição e deverão preparar-se como tal! Viver e tocar com dor não é uma inevitabilidade, é uma opção.

A prevalência de dor e lesões nos músicos

À medida que os anos passam e as horas agarrados ao instrumento se acumulam, é quase inevitável que os músicos profissionais desenvolvam em determinado momento da sua carreira problemas musculoesqueléticos e/ou neuromusculares de gravidade variável. Isto se não fizerem nada no que concerne à sua preparação física. Estudos de revisão sobre a prevalência de lesões em músicos profissionais apontam para que 76% dos músicos sofrem ou sofreram de problemas físicos que os impedem de actuar ao seu nível habitual e 84% tiveram lesões que interferiram negativamente com a sua prática musical1. Alguns músicos ficar-se-ão por tendinopatias e lombalgias de intensidade variável que conseguirão gerir à custa da toma crónica de medicamentos anti-inflamatórios ou simplesmente tocando menos frequentemente e suportando dor e desconforto. Outros, desenvolverão síndromas lesionais por sobreuso mais graves que se tornarão crónicos e comprometerão não só a qualidade da performance, mas também a qualidade de vida, obrigando a períodos de inactividade musical. Outros ainda, sofrerão de formas de lesão ainda mais graves que poderão resultar no abandono da carreira como músico instrumentista.

De uma forma geral, lesões mais frequentes em instrumentistas afectam e manifestam-se através de dor e/ou disfunção sobretudo das articulações, tendões, ligamentos e nervos do membro superior, cabeça, pescoço e coluna. Por exemplo, em instrumentistas de orquestra as lesões de origem músculo-esquelética e/ou neuromuscular são mais comuns afectando cerca de 64% dos músicos, dos quais 20% são problemas do foro nervoso periférico e cerca de 8% são casos de distonia focal2 . O que faz sentido, tendo em conta que essas são as zonas do corpo mais stressadas durante a prática instrumental. Excepção feita à distonia focal, que apesar de poder estar acompanhada de dor e lesão músculo-esquelética, a origem da disfunção observada a nível periférico é, na verdade, central, ou seja, os circuitos neuronais disfuncionais estão comprometidos logo nos níveis superiores do sistema nevoso central como o córtex cerebral. Assim, as lesões mais frequentes em músicos instrumentistas podem ser resumidas da seguinte forma3:

- Lesões músculo-esqueléticas – epicondilite, tendinopatias (tendinose, tendinite, tenossinovite), bursite, artrite, artrose, osteoartrite, contracturas, lesões na articulação temporomandibular;

- Bloqueio e inflamação nervosa – síndroma do túnel cárpico, síndroma do desfiladeiro torácico, síndroma do túnel radial, síndroma de compressão do nervo ulnar, síndroma do túnel ulnar, radiculopatias cervicais e lombares;

- Hipermobilidade;

- Distonia focal;

- Perda de audição.

O surgimento de lesões nos músicos deve-se a um conjunto de factores que, naturalmente, interagem. Vários autores identificaram os seguintes factores como facilitadores e/ou provocadores do surgimento de lesões nos músicos1:

- Factores fisiológicos e biológicos como género e idade. As mulheres instrumentistas parecem ter maior propensão para desenvolver lesões músculo-esqueléticas e nervosas periféricas em relação aos homens, e indivíduos que iniciem precocemente a prática instrumental com elevado volume, aos 4-5 anos de idade, também têm maior probabilidade de desenvolver lesões mais tarde na sua carreira4,5. No caso da distonia focal há uma prevalência clara no sexo masculino (acima de 90%) e em mulheres com distúrbios menstruais, o que sugere que factores hormonais podem ser predisponentes para o desenvolvimento desta patologia6.

- O tipo de instrumento. As características do instrumento (tamanho, forma e peso) e o tempo de prática implicam níveis diferentes de exigência física, em que a fadiga instalada e a execução em esforço podem levar ao desenvolvimento de lesões7. Por exemplo, a posição inerente a tocar clarinete implica que todo o peso do instrumento esteja suportado sobre o polegar direito, e ao mesmo tempo requer uma grande quantidade de movimentos curtos e rápidos dos dedos de ambas as mãos8. Outro exemplo que me diz especial respeito, é o contrabaixo de cordas. Um instrumento volumoso com uma coluna de ar de inércia considerável, que requer não só considerável força de preensão da mão que pisa as cordas, como um esforço físico (que na verdade se quer minimizar em favor de uma técnica de execução o mais eficiente possível) para fazer movimentar essa coluna de ar e fazer o instrumento vibrar e produzir som. Quem já experimentou tocar contrabaixo alguns minutos percebe bem a dimensão física que o instrumento poderá ter.

- Técnica instrumental. Uma técnica de instrumento débil, com posições não optimizadas, mais baseada em esforço físico do que numa técnica eficiente, associada a longas horas de prática sem descanso, vai naturalmente predispor o instrumentista à dor e à lesão sobretudo nos pulsos, mãos, pescoço e ombro9.

- A exigência performativa. A exigência técnica de uma determinada peça musical que muitas vezes requer uma execução a elevada velocidade, elevada intensidade, com fatigante repetição de movimentos ou manutenção de posições extremas das mãos durante um largo período de tempo. Tudo isto é gerador de stress mecânico e poderá ser causador de lesão 10,11.

- Assimetria corporal. Da mesma forma que um atleta de modalidades com enfoque unilateral irá tentar compensar essas assimetrias trabalhando os dois lados do corpo, um músico encontra-se numa situação semelhante, pois tocar um instrumento implica um trabalho assimétrico em posições muito pouco naturais por longos períodos de tempo, favorecendo a instalação de vários desequilíbrios musculares12.

- Má condição física. Bons níveis de força e uma boa condição geral é essencial para manter uma boa posição ao tocar um instrumento durante longos períodos de tempo. Posições essas, na sua maioria, muito pouco naturais. A melhoria da condição física irá permitir resistir ao instalar da fadiga, recuperar mais rapidamente entre ensaios ou sessões de estudo, e na verdade, irá permitir tolerar mais horas de prática sem deterioração da técnica musical e performance7. Desequilíbrios e fraqueza musculares resultante das longas horas sentado, da manutenção de certas posições e da repetição exaustiva de movimentos curtos devem ser tratados através de programas de treino que incluam exercícios que fortaleçam o corpo de forma global e que, ao mesmo tempo, visem compensar desequilíbrios musculares específicos induzidos pela prática instrumental13.

- Outros factores de estilo de vida. Sabemos que aspectos do estilo de vida como fumar ou exposição ao fumo, consumo de álcool, privação de sono, má nutrição, má hidratação e obesidade têm efeitos muito nefastos a nível sistémico no nosso corpo. No que concerne ao desenvolvimento de lesões do foro neuromuscular, sabemos que todas estas formas de toxicidade fragilizam todo o tecido conjuntivo (cartilagem, tendões, ligamentos, membranas), os músculos e a condução nervosa, predispondo à ocorrência de processos inflamatórios localizados e ao desenvolvimento de lesões crónicas. Sabia que, por exemplo, a obesidade predispõe grandemente para o desenvolvimento da síndrome do túnel cárpico?14 Ou que fumar está fortemente associado ao desenvolvimento de lesões e disfunções no ombro?15

Prevenir e resolver lesões nos músicos

Qualquer atleta de elite sabe empiricamente algo que há muito tempo é corroborado pela ciência. Que a forma mais eficaz de prevenir (e também curar) lesões de sobreuso ou sobrecarga devido à prática desportiva com elevado volume é garantir uma boa condição física de base aliada a bons hábitos de recuperação, descanso e nutrição. No que concerne à sua condição física, não passa pela cabeça de um atleta de elite, não seguir um programa regular de desenvolvimento das qualidades físicas. Ele sabe que isso terá consequências negativas quer no seu rendimento desportivo, quer na sua susceptibilidade para desenvolver lesões. Ele sente na pele que quanto mais fraco o seu sistema músculo-esquelético se encontrar, mais susceptível estará de se lesionar devido ao elevado volume a que a sua prática desportiva de alta performance obriga. A pergunta que se impõe é, e se considerarmos que a actividade em que os músicos profissionais incorrem constitui uma actividade de alta performance física e mental que obriga a largas horas de prática diária, não deverão os músicos tratar-se como atletas de alto rendimento? Eu tenho a certeza que sim.

De facto, numa revisão sistemática de 2019 sobre treino físico para músicos profissionais de orquestra1, os autores indicam que seguir um programa de treino físico estruturado de durações variadas (desde algumas semanas a vários meses), resultou, de uma forma geral, em melhorias significativas na performance e na redução (e mesmo eliminação) de dores crónicas.

Para manter-se a tocar ao mais alto nível e por muito tempo, os músicos beneficiariam muito se se tratassem como atletas de alto rendimento. Garantir que se mantêm em boa forma física conjugado com bons hábitos de recuperação, descanso e nutrição. E atenção, quando falo em manter-se em boa forma física não me refiro a praticar desporto. Aliás, praticar desporto como forma de melhorar a condição física não é ideal e até pode ser prejudicial. Pois estar-se-á a adicionar mais uma actividade com características assimétricas a outra também ela assimétrica que é tocar um instrumento musical. Em geral, todos os desportos são por definição constituídos por movimentos especializados, e por isso mesmo, assimétricos. Por isso, a não ser por razões meramente lúdicas (que também pode ser positivo a um nível mental), a prática de um desporto como estratégia para melhorar a condição física não é ideal e não deve ser a forma escolhida em especial pelos músicos (abordo esta questão neste artigo: Porque é que os músicos não devem fazer desporto?).

A condição física geral de base melhora-se através do treino das qualidades físicas. Isto pressupõe uma avaliação da situação inicial para aferir as limitações específicas e delinear uma estratégia de intervenção. Há que começar sempre pela base e progredir a partir daí, tal como o processo de aprender a tocar um instrumento musical. Aqui, a atenção ao detalhe é fundamental. Uma estratégia bem delineada implica uma gestão das variáveis do treino específica para a condição e objectivos do atleta ou, neste caso, do músico. É crucial uma correcta selecção de exercícios, e monitorização de perto da sua implementação quanto à forma de execução, carga utilizada e progressão ao longo do tempo. Como referi, não é muito diferente do processo de aprender a tocar um instrumento musical!

Para um músico, tocar o instrumento é a prioridade das prioridades. Pode ser obsessivo, eu sei. Mas tocar melhor e no longo prazo não passa necessariamente por tocar mais horas, mas por investir em cuidar da ‘’máquina’’ que é o nosso corpo. Volto a reforçar que tocar com dor ou desconforto é uma opção e não uma inevitabilidade. Cuidem do vosso corpo e tratem-no bem, pois irão precisar dele no longo prazo!

Bons ensaios e bons treinos!

Nuno Correia

Referências:

- Gallego, C., Ros, C., Ruíz, L., Martín, J. (2019). The physical training for musicians. Systematic review. Sportis Sci J, 5 (3), 532-561.

- Lederman, R. J. (2003). Neuromuscular and musculoskeletal problems in instrumental musicians. Muscle & Nerve, 27(5), 549–561.

- Betancor Almeida, I. (2011). Hábitos de actividad física en músicos de orquestas sinfónicas profesionales: un análisis empírico de ámbito internaciona Tesis Doctoral. Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria.

- Fishbein, M., Middlestadt, S., Ottati, V., Straus, S., y Ellis, A. (1988). Medical problems among ICSOM musicians: Overview of a national survey. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 3(1), 1–8.

- Viaño, J. J. (2004). Estudio de la relación entre la apariciación de lesiones musculoesqueléticas en músicos instrumentistas y hábitos de actividad física y vida diaria. En III Congreso De La Asociación Española de Ciencias Del Deporte. Valencia: Universidad de A Coruña.

- Rosset-Llobet, J., Candia, V., Fàbregas, S., Ray, W., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2007). Secondary motor disturbances in 101 patients with musician’s dystonia. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry, 78(9), 949–953.

- Sardá, E. (2003). En forma: ejercicios para músicos. Barcelona: Paidos.

- Thrasher, M., y Chesky, K. (1998). Medical problems of clarinetists: Results from the U.N.T. musician health survey. The Clarinet, 25(4), 24–27.

- Wynn, C. B. (2004). Managing the physical demands of musical performance. En Williamon A. (Ed.), Musical excellence: Strategies and techniques to enhance performance (pp. 41–60). Londres: Oxford University Press.

- Bejjani, F. J., Kaye, G. M., y Benham, M. (1996). Musculoskeletal and neuromuscular conditions of instrumental musicians. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 77(4), 406–413.

- Mark, T., Gary, R., y Miles, T. (2003). What every pianist needs to know about the body: a manual for players of keyboard instruments: piano, organ, digital keyboard, harpsichord, clavichord. GIA Publications. Martín.

- Ackermann, B., Adams, R., y Marshall, E. (2002). Strength of endurance training for undergraduate music majors at a university? Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 17(1), 33– 41.

- Frabretti, C., y Gomide, M. F. (2010). A saúde dos músicos: dor na prática profissional de músicos de orquestra no ABCD paulista. Revista Brasileira de Saúde Ocupacional, 35(121), 33– 40.

- Shiri R, Pourmemari MH, Falah-Hassani K, Viikari-Juntura E. The effect of excess body mass on the risk of carpal tunnel syndrome: a meta-analysis of 58 studies. Obes Rev. 2015;16(12):1094-1104.

- Bishop, Julie Y. et al. (2015). Smoking Predisposes to Rotator Cuff Pathology and Shoulder Dysfunction: A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy, Volume 31, Issue 8, 1598 – 1605.

Após as últimas semanas de isolamento que vivemos, prepara-se agora gradualmente o regresso à normalidade. Uma normalidade que será ainda bastante diferente daquilo que conhecíamos, pedindo-se, nesta fase, que se aprenda a conviver com o vírus.

Ora bem, tendo em conta que o vírus veio para ficar e que vamos ter efetivamente de viver com ele, nunca foi tão importante cuidar da sua alimentação e estilo de vida para que o seu sistema imunitário tenha todas as ferramentas necessárias para combater este vírus de forma eficaz, caso haja um possível contágio.

Em primeiro lugar, é importante perceber, de forma muito simplista, como funciona este vírus. O SARS-CoV-2 tem a habilidade de estimular uma libertação descontrolada de citocinas pró-inflamatórias, levando a um efeito de tempestade de citocinas, causando lesão tecidual e danos graves no epitélio respiratório.

Assim sendo, parece que a palavra a reter é inflamação, sendo esta a causa dos danos graves e mesmo da morte. Extrapolando um pouco o raciocínio, quem sofre contágio com um status inflamatório mais elevado, está, à partida, em maior risco de sofrer danos mais severos. E é isso que se tem observado! As pessoas com comorbilidades, nomeadamente obesidade, doenças autoimunes, hipertensão arterial, cancros, são considerados grupos de risco para esta pandemia e possuem, também todos eles, estados inflamatórios mais acentuados.

Portanto, a chave parece ser trabalharmos nos nossos estilos de vida, para melhorarmos o nosso status inflamatório e assim diminuirmos o risco de sofrer de uma doença crónica não transmissível. Ao mesmo tempo, é importante fornecermos as ferramentas para que o nosso sistema imunitário seja capaz de uma resposta adequada em caso de contágio. Como é que isso se faz?

Em primeiro lugar, e isto é, de longe, o ponto mais importante de todo este artigo. O grande segredo, o grande milagre, a pílula mágica para melhorar a sua alimentação do dia para noite é só um, coma COMIDA! Mas comida de verdade, daquela que não tem ingredientes, nem rótulos, nem marketing ou alegações de saúde. Falo de carne, peixe, marisco, ovos, vegetais, fruta, oleaginosas. Simples assim!

Comer comida de verdade deixa-o num ponto muito mais à frente que a grande maioria das outras pessoas no que toca à capacidade de resposta do seu sistema imunitário. Isto porque, quando comemos alimentos de verdade, o seu organismo recebe uma panóplia variada de vitaminas, minerais, antioxidantes, fitoquímicos, polifenóis, tudo aquilo que o organismo necessita para funcionar de forma correta. No entanto, e tendo em conta as necessidades e os requisitos específicos de cada indivíduo, é de extrema importância a individualização, razão pela qual é essencial ser acompanhado por um profissional da área da nutrição.

Outro ponto de extrema importância e que está diretamente relacionado com o anterior: a nossa imunidade começa no intestino e, portanto, ter um microbiota diversificado e saudável e uma mucosa intestinal íntegra é essencial. Sabemos que o microbiota é um grande responsável pelo status inflamatório do organismo, sendo, portanto, de máxima importância cuidarmos das nossas bactérias intestinais.

Para tal, é essencial o consumo adequado de fibra, solúvel e insolúvel. E portanto, voltamos a falar de frutas e vegetais! Estas deverão estar presentes em grandes quantidades na dieta de todos nós. Para além da fibra, o consumo de alimentos fermentados deve ser incentivado, nomeadamente vegetais fermentados (como por exemplo chucrute), kombucha e kefir, como forma de modular o microbioma e reparar a mucosa intestinal.

Tendo em conta que o vírus SARS CoV-2 é relativamente recente, ainda não são muitos os estudos que nos mostrem quais os compostos ativos que têm uma ação direta no vírus. No entanto, conhecendo o mecanismo de atuação do SARS CoV-2, podemos aferir ou deduzir quais os compostos que vão atuar na diminuição da capacidade do vírus infetar as nossas células, diminuir a replicação viral e dar suporte ao nosso sistema imunológico.

Assim sendo, existem alguns compostos ativos, vitaminas e minerais que atuam nestas diferentes vias. Alguns destes compostos podem ser obtidos através de suplementação específica e outros através da alimentação. No entanto, é preciso relembrar que a suplementação deve ser prescrita por um profissional de saúde, tendo em conta as necessidades e o historial clínico de cada um. Não é adequado tomar suplementos sem haver um motivo clínico que o justifique.

Naturalmente que nenhum destes suplementos impede o contágio e, neste sentido, apenas as medidas de higiene adequadas e o distanciamento social são eficazes. Não obstante, em caso de contágio, o nosso sistema imunitário tem de ser o mais eficaz a combater o vírus e a diminuir os sintomas associados.

Os seguintes nutrientes e compostos ativos de forma isolada parecem ser grandes aliados:

Vitamina A: desempenha um papel importante na função imune, regulando as respostas imunes celulares e humorais (Huang et al., 2018). A nível alimentar pode ser encontrada nas vísceras dos animais, como fígado, e nas gemas dos ovos. A suplementação só deve ser considerada caso se confirmem défices a nível sérico.

Vitamina C: contribui para a defesa imunológica, melhorando a quimiotaxia e fagocitose (Beveridge, Wintergerst, Maggini and Hornig, 2008). A suplementação com vitamina C pode não ser necessária caso a ingestão alimentar seja adequada. Para isso, é necessário consumir frutas e vegetais ricos em vitamina C ao longo do dia, nomeadamente kiwis, citrinos, morangos, pimentos, agrião e salsa.

Vitamina D: participa na modulação da resposta tanto do sistema imune inato como adaptativo. Parece haver uma relação entre o status de vitamina D do indivíduo e a resposta antiviral contra infeções respiratórias (Jayawardena et al., 2020). A suplementação só deve acontecer caso existam défices, mas esta é muitas vezes necessária, especialmente durante os meses de Inverno.

Zinco: participa no funcionamento do sistema imunitário e diminui a replicação viral, reduzindo a gravidade das infeções. A deficiência de zinco está assim associada a uma maior susceptibilidade a infeções virais (Read, Obeid, Ahlenstiel and Ahlenstiel, 2019). No entanto, e uma vez mais, a suplementação só deve ser feita caso se verifiquem défices comprovados deste mineral. Na alimentação, pode ser encontrado nas ostras, na carne vermelha e nas sementes de girassol.

Selénio: possui propriedades anti-inflamatórias e um efeito antioxidante. A deficiência de selénio está associada com uma função imune mais débil (Rayman, 2012). O consumo diário de castanhas do Brasil pode auxiliar na obtenção de valores adequados de selénio no organismo.

Melatonina: tem um efeito antioxidante e anti-inflamatório e promove uma diminuição nas citocinas inflamatórias em circulação (Zhang et al., 2020). A suplementação pode ser necessária, dependendo das necessidades do indivíduo.

Estas são algumas das estratégias a aplicar em termos alimentares. No entanto é importante (re)lembrar que as mudanças a efetuar devem ser de estilo de vida, onde se devem incluir hábitos de exercício físico regular, adequação de padrões de sono, gestão de stress e diminuição da exposição a toxinas. Todas estas alterações contribuirão para a diminuição da inflamação e para melhoria da função do sistema imunitário, tão importante para os tempos actuais e para a melhoria da nossa qualidade de vida.

Andreia Luís de Castro

Referências:

Beveridge, S., Wintergerst, E., Maggini, S. and Hornig, D., 2008. Immune-enhancing role of vitamin C and zinc and effect on clinical conditions. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 67(OCE1).

Huang, Z., Liu, Y., Qi, G., Brand, D. and Zheng, S., 2018. Role of Vitamin A in the Immune System. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 7(9), p.258.

Jayawardena, R., Sooriyaarachchi, P., Chourdakis, M., Jeewandara, C. and Ranasinghe, P., 2020. Enhancing immunity in viral infections, with special emphasis on COVID-19: A review. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews, 14(4), pp.367-382.

Rayman, M., 2012. Selenium and human health. The Lancet, 379(9822), pp.1256-1268.

Read, S., Obeid, S., Ahlenstiel, C. and Ahlenstiel, G., 2019. The Role of Zinc in Antiviral Immunity. Advances in Nutrition, 10(4), pp.696-710.

Zhang, R., Wang, X., Ni, L., Di, X., Ma, B., Niu, S., Liu, C. and Reiter, R., 2020. COVID-19: Melatonin as a potential adjuvant treatment. Life Sciences, 250, p.117583.

Given the times we live in, where social contact is limited, the promotion of online services in all professional areas proliferates. In fitness, it seems that it has suddenly been discovered that you can (and should) train every day and that you can train at home and/or on your own. It is incredible the explosion of posts on social media by personal trainers offering sequences of exercises for people to perform at home. We know that, for better health and resilience, it is essential to exercise every day, just as it is essential to eat well and maintain personal hygiene, but this has always been so and, therefore, it is not only a necessity of current times.

For this reason, posting an exercise line-up for everyone to perform is as valuable as posting a photo of a meal or of someone brushing their teeth. It serves as much to remind you that these activities are important, but the content is not, to a large extent, applicable to you reading this text. Much less when it comes to exercise. In fact, picking up the fork and knife to eat, or the act of brushing your teeth are less complex activities than performing most of the physical exercises that we often see proposed, let alone organizing them in a training session.

The health and resilience resulting from training is even more relevant in times of crisis such as the one we are experiencing now, but that health and resilience was mainly built months and years prior to this moment. Notably during those months and years that you consistently went to the gym to do your workout, often with personal sacrifice. It is hard to organize oneself in order to be able to train! We have family and work and it is sometimes difficult to reconcile all social and professional obligations with the time we choose to invest in our health and well-being, like in the case of training. Notice that now I’m using the term training.

Because many of you who are reading these lines have long understood the difference between “exercising” and training. Many of you have realized that “exercising” is better than nothing, but that training is at a higher level. Training is a process that requires the organization and management of a range of variables over time. It requires making a careful assessment of the initial condition, selecting specific exercises and the ways to perform them, observing and evaluating movement, and making the necessary adjustments (e.g. load, type and form of exercise execution) in order to ensure constant progression along the path towards health, performance and resilience. Training is not the same as ‘’doing exercises” always varied and without criteria just to maintain some physical activity. And because some of you understand this difference, you have come over the months and years that preceded today’s turbulent times to make organizational sacrifices in order to train. And you chose to invest a little more of your time and money, and regularly went to a gym to get a training service. A service in which a program is followed, the exercises are not chosen at random, and in which the progression in the loads used as well as the execution of the exercises is closely monitored by a coach.

All the benefits of personalized training are possible to obtain remotely via online. I believe that the in-person format will always be superior, but with good organization and commitment from both the coach and student, constant progression is possible, and this difference can be mitigated. How do we know this at The Strength Clinic? Because we’ve been doing it for years! In addition, personalized training followed online may even have some advantages over the face-to-face format, such as:

- Not having to go to the gym at any given time. This can be a great advantage for some people. If the self-discipline of following your training program is guaranteed, travel time and what it implies in organizational terms is saved. In addition, you can choose a training time slot that best fits your schedule without being conditioned by the availability of your coach;

- Greater consistency and commitment doing the exercises in your program. Since you can choose the time slot of your training session, you are less likely to miss it, as you will have more flexibility in adjusting the schedule if needed. This way, it is more likely that you reach the weekly training frequency that is desirable. In addition, as we recommend that you document on video a summary of each workout on an online platform so that your coach can observe, this also adds an additional sense of commitment to the session and the proper execution of the exercises;

- Better cost benefit. In fact, you will be able to enjoy almost all the benefits of having a personal trainer for a lower price because you will not have to pay for the running costs of the facility and its equipment usage where the in-person training session would take place;

- Train directly with your favorite coach. If the coach you would like to work with is not available in-person or his/her in-person rate is beyond your means, the online option will allow you to work directly with him for a lower price.

The message “don’t stop training even if you are at home or on your own” in the context of the crisis we are experiencing today is correct! However, this need did not arise today. It is something that should be part of our lives if we want to remain getting stronger and healthier forever. For this purpose, training is much better than just “exercising”, especially if you follow workouts taken from social media that do not take into account your specific profile, your body awareness and do not follow any criteria for exercise selection and future programming. It only serves the purpose of “moving the body” and getting tired in that moment or day, but it will not accomplish much more than that. Because training implies a process that is based on your goals and individual characteristics. In a training session, what you do today was based on what you did yesterday and what you are going to do in the future. And it is possible to continue to train online and reap all the benefits of personalized training, even at a distance. It requires a mutual commitment of the student and coach in a process that is joint. Your optimized personal development will always be our commitment at The Strength Clinic. We are here to guide you through this process rather that offering “one size fits all” workouts for everyone!

Stay strong!

Nuno Correia

Este artigo é técnico e específico, se aquilo que pretende é apenas saber o que precisa fazer, pode ir directamente para a conclusão. Se, porventura, quiser educar-se um pouco mais sobre o potencial do exercício na sua saúde e imunidade, recomendo que vá buscar um café ou um chá e que leia o artigo completo.

Introdução

Uma das questões mais recorrentes nos últimos tempos em virtude do tema “Coronavírus” é se o exercício físico pode melhorar a função do sistema imunitário. Mas vamos recuar primeiro um pouco no tempo. A necessidade de se movimentar ou de fazer exercício para manter ou melhorar a saúde não é nova. O movimento sempre foi e sempre será uma necessidade essencial à condição humana. O problema actual é que no nosso estilo de vida moderno (altamente sedentário) a maior parte das pessoas esqueceu-se disso, deixou de alimentar a sua motricidade e pensa que consegue resolver os seus problemas de saúde com soluções rápidas ou temporárias de fitness.

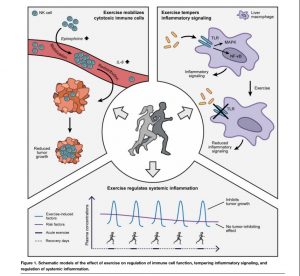

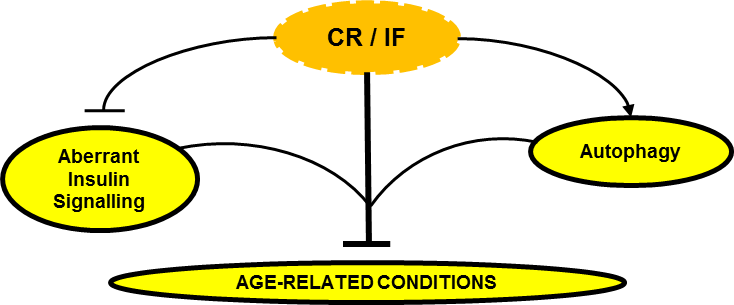

Ou seja, se sabemos que o exercício tem a possibilidade de afectar todos os órgãos e sistemas do corpo humano, é natural (e desejável) que o sistema imunitário seja também regulado pelo nível de actividade física de cada indivíduo. A inactividade física em conjunto com a perda de massa muscular (e alimentação deficiente) irá facilitar a imunosenescência, a perda de função do sistema imunitário. Clinicamente, isto significa um maior risco de infecções, reactivações mais frequentes de vírus latentes, diminuição da eficácia da vacinação e aumento da prevalência de doenças auto-imunes e cancro1.

Portanto, temos por um lado o movimento ou a actividade física, que é transversal à evolução de qualquer homo sapiens e, por outro, temos o treino físico, que pode ser o catalisador para elevar os resultados da performance humana para outros patamares. A percepção geral de que a actividade física regula o sistema imunitário é correcta mas a ideia generalizada de que qualquer forma de exercício melhora o sistema imunitário é incorrecta. Simplesmente não podemos ignorar os princípios elementares da biologia humana e do ciclo de stress, recuperação e adaptação inerentes a cada indivíduo.

Contextualização da imunologia do exercício

Embora a imunologia do exercício seja considerada (relativamente) uma nova área de investigação científica, com 90% dos trabalhos publicados após 19902, alguns dos primeiros estudos foram publicados há mais de um século. Por exemplo, em 1902, Larrabee3 demonstrou que as alterações nas contagens diferenciais de glóbulos brancos nos corredores de maratona de Boston eram semelhantes às observadas em certas condições de doença, com uma “considerável leucocitose do tipo inflamatório”.

De acordo com a revisão efectuada por Nieman4, uma das maiores autoridades mundiais em imunologia do exercício, e que por acaso já correu mais de 50 maratonas, as descobertas científicas neste campo podem ser divididas em quatro períodos distintos. De 1900 a 1979, o foco era nas alterações agudas e na função das células imunitárias. De 1980 a 1989, vários estudos sugeriram que o esforço de intensidade elevada estava associado com uma disfunção imunitária transiente, com a elevação de biomarcadores inflamatórios e com um aumento do risco de infecções do trato respiratório superior. Durante o período de 1990 a 2009, foram adicionadas outras áreas complementares de estudo, incluindo o efeito interactivo da nutrição, os efeitos do exercício no envelhecimento do sistema imunitário e as influências nas citocinas inflamatórias. A partir de 2010, com os avanços na espectometria de massa e na tecnologia associada aos testes genéticos, começou-se a depositar maior atenção em áreas de estudo como a metabolómica, lipidómica, proteómica e microbioma, com o intuito de fornecer directrizes mais personalizadas ao nível da nutrição e exercício.

Portanto, já sabemos há muito tempo que o sistema imunitário é muito sensível ao exercício físico e, como tal, será a extensão e a intensidade do exercício, que vão reflectir o nível de stress fisiológico imposto ao sistema imunitário. Claramente, durações e intensidades elevadas em simultâneo não fazem bem à saúde.

O envelhecimento e o seu impacto na imunosenescência

A deterioração do sistema imunitário com a idade deve-se principalmente a factores biológicos, como a genética e às interacções com factores ambientais (como a exposição a agentes infecciosos, incluindo citomegalovírus), impondo alterações metabólicas causadas por estilos de vida não saudáveis (exercício inadequado, dieta inadequada) e stress fisiológico prolongado5,6.

A imunosenescência associada ao envelhecimento acontece pelo menos através dos seguintes três fenómenos: 1) redução na resposta imunitária; 2) aumento da inflamação e oxidação (em inglês inflammaging e oxi-inflammaging); 3) produção e libertação de auto-anticorpos.

No caso do primeiro, o envelhecimento influencia principalmente a imunidade através de alterações na estrutura e actividade do timo (i.e., atrofia do timo), uma glândula com importantes funções imunitárias localizada entre os pulmões, da redução na produção de linfócitos (linfopoiese primária)7,8, do declínio das células T ingénuas, da acumulação das células T memória e de uma diminuição na produção de anticorpos9-11. O envelhecimento também está associado ao declínio das células estaminais hematopoiéticas (hemocitoblastos) e à função das células progenitoras, resultando num aumento da produção de células da linhagem mielóide e diminuição no potencial linfóide12.

No que diz respeito ao segundo, o envelhecimento poderá contribuir para o aumento da secreção de citocinas inflamatórias (interleucina-1 [IL-1], factor de necrose tumoral alfa [TNF-α], interleucina-6 [IL-6] e proteína C reactiva [PCR])13. Com o avançar da idade, os macrófagos, que actuam como sentinelas e residem nos tecidos conjuntivos e orgãos do corpo, tornam-se mais pró-inflamatórios, libertando maiores quantidades de TNF-α e de interleucina-12 (IL-12)14, o que pode acelerar os danos nos tecidos.

Finalmente, no que concerne ao terceiro, o aumento da produção e libertação de auto-anticorpos poderá levar a um aumento de manifestações auto-imunes15,16.

Efeitos do exercício na imunosenescência

Muitos trabalhos têm demonstrado que um estilo de vida fisicamente activo pode ter efeitos positivos no envelhecimento do sistema imunitário17,18. Em particular, o exercício físico regular parece afectar os processos de envelhecimento do sistema imunitário inato (também chamado de não específico) e adaptativo (também chamado de específico ou adquirido). Por exemplo, um dos testes mais robustos para medir a competência imune é a resposta mediada por anticorpo ou célula a novos antígenos, frequentemente administrados experimentalmente por vacinação. As respostas humorais (imunidade mediada pelos linfócitos B) e celulares (imunidade mediada pelos linfócitos T) à vacinação parecem ser mais fortes nos indivíduos activos em comparação com os indivíduos sedentários e mais fortes também naqueles que realizaram formas de exercício estruturado nos meses que antecederam a administração da vacina19,20.

O exercício regular no envelhecimento parece estar associado a um melhor funcionamento das células natural killer (NK)21, a primeira classe de glóbulos brancos a actuar em resposta a qualquer vírus, bactéria ou tumor. Da mesma forma, o funcionamento dos neutrófilos parece ser afectado positivamente, uma vez que idosos saudáveis e mais activos têm uma melhor migração de neutrófilos em direcção à interleucina-8 (IL-8)22, uma citocina com efeitos na angiogénese23 (formação de novos vasos sanguíneos) e, potencialmente, no desenvolvimento muscular. As intervenções com exercício demonstraram diminuir o número de monócitos inflamatórios circulantes CD16+24 (o termo CD significa “cluster of differentiation” e surgiu como forma de diferenciar as diferentes classes de células imunológicas) e a melhorar a função dos neutrófilos e a fagocitose em pacientes com artrite reumatóide25.

Estudos transversais antigos em idosos demonstraram que mulheres altamente treinadas mostraram uma melhoria na proliferação de células T induzidas por mitógeno em comparação com um grupo não treinado21. A melhoria da proliferação das células T também foi relatada noutro estudo de corredores idosos que treinaram uma média de 17 anos. Estes resultados foram associados com um melhor funcionamento do sistema imunitário adaptativo26 e sugerem que uma capacidade cardiovascular aumentada previne a acumulação de células T senescentes.

Devido a estas descobertas, Minuzzi et al.27 recrutaram 19 atletas master (mais de 40 anos) com 20 anos de experiência de treino e compararam o seu sistema imunitário com um grupo de controle sedentário composto por dez indivíduos com idades aproximadas. Neste estudo, os investigadores concluiram que o exercício tem a capacidade de não apenas prevenir a acumulação das células T senescentes ao longo da vida, como também de potenciar a sua exclusão através de mecanismos como a apoptose. Assim, estes dados revelam-nos que o treino físico regular é capaz de reverter as alterações associadas com a idade nas subpopulações de linfócitos e de reduzir parcialmente o declínio das funções das células T relacionadas com a idade.

Num estudo57 publicado recentemente (Março 2020), com dados recolhidos num hospital de Whuan (China), aparentemente a cidade que se tornou o epicentro da pandemia covid-19, os autores sugeriram que a linfopenia (contagem reduzida de linfócitos no sangue) é um indicador eficaz para predizer a severidade dos sintomas do covid-19 e propuseram um modelo de classificação de risco com base na percentagem de linfócitos no sangue. Neste trabalho, os autores verificaram que os indíviduos com uma percentagem de linfócitos mais baixa, tinham pior prognóstico e maior risco de mortalidade.

O músculo esquelético como um órgão imuno-regulador

O músculo esquelético é reconhecido como um órgão endócrino capaz de expressar e secretar citocinas (conhecidas como miocinas ou mioquinas) no sistema circulatório durante a actividade física28. A interleucina-6 (IL-6) foi a primeira miocina identificada e pode ser considerada uma das mais eficazes na regulação do sistema imunitário. A IL-6 é produzida logo após o início da actividade física e os níveis produzidos dependem de vários factores como a intensidade do exercício, a duração do exercício e a quantidade de massa muscular utilizada29. Na verdade, as nossas células musculares já produzem IL-6 basal mas o exercício pode aumentar essa libertação em mais de 100 vezes30.. Mas há aqui uma questão muito importante a destacar e que normalmente gera alguma confusão. Por um lado, a IL-6 produzida através das contracções musculares exerce um potente efeito anti-inflamatório (via c-Jun terminal kinase/activador proteína-131) que leva à produção de outros mediadores regulatórios como interleucina-10 (IL-10), receptor antagonista da interleucina-1 (IL-1RA) e à inibição do factor de necrose tumoral alfa (TNF-α) pelos monócitos e macrófagos32,33. Mais, a IL-6 também estimula a libertação de cortisol pelas glândulas supra-renais, proporcionando assim um segundo sinal anti-inflamatório34. Por outro lado, a IL-6 derivada da via de sinalização factor nuclear-kB (NF-kB35) tem um efeito pró-inflamatório e está naturalmente associada a estados de inflamação crónica e de fraca saúde. Recentemente, numa análise a 150 pacientes infectados de dois hospitais em Whuan (China), Ruan et. al.58, verificaram que as concentrações de IL-6 diferiam significativamente entre sobreviventes e não sobreviventes do covid-19, com os não sobreviventes a registar valores 1,7 vezes mais altos, indicando que a IL-6 elevada (não aquela derivada das contracções musculares) também tem repercussões negativas na imunidade. Pode fazer algumas respirações diafragmáticas agora 🙂

Além da IL-6, outras citocinas como a interleucina-736 (IL-7) e interleucina-1537 (IL-15), expressam-se também através das contracções musculares. A IL-7 é necessária para o desenvolvimento de timócitos38 e tanto a IL-7 como a IL-15 são factores proliferativos de linfócitos (especialmente para as células T ingénuas39), que têm tendência a diminuir com a idade e com a inactividade física40. A IL-15 proveniente do músculo ainda aumenta a actvidade das células natural killer (NK) e tem uma influência na redução de gordura através da inibição da lipogénese41. Outras miocinas libertadas pelos músculos também têm sido apontadas na literatura pelos seus efeitos metabólicos e imunológicos, contudo é importante ter presente que os músculos podem segregar mais de 600 miocinas e que ainda há muito por investigar nesta área de estudo, a que alguns autores já designam de “miocinoma”42.

De facto, o treino ao longo da vida também parece afectar os níveis basais de citocinas pró e anti-inflamatórias. Neste estudo levado a cabo por Minuzzi et. al.43, que teve como objectivo analisar os efeitos do envelhecimento e do treino ao longo da vida nas principais citocinas pró e anti-inflamatórias, ficou expresso que os níveis de IL-1RA, interleucina-1 beta (IL-1β), interleucina-4 (IL-4) e interleucina-8 (IL-8) de atletas master estavam mais equilibrados quando comparados com dois grupos sedentários de idade semelhante e de idade mais jovem.

Portanto, o músculo esquelético deve ser visto como a nossa farmácia endógena, um património importante a preservar ao longo da vida que vai ajudar a aumentar a imunidade. Uma reserva de nutrientes e aminoácidos que vai defender o corpo em situações de doença e na recuperação de qualquer evento traumático. Logo, um investimento no desenvolvimento de saúde e imunidade passa desde logo por manter a massa muscular e um estilo de vida activo.

Efeitos agudos e efeitos crónicos do exercício na imunidade

A evidência indica que os mecanismos associados à alteração da função imunitária com o exercício estão relacionados com vários factores, como estímulos do sistema neuroendócrino (catecolaminas, cortisol), estímulos metabólicos (i.e., hidratos de carbono, antioxidantes ou prostaglandinas)44,45, bem como com o débito cardíaco, fluxo sanguíneo, pressão arterial, forças de cisalhamento, entre outros. Alguns estudos parecem sugerir que os efeitos agudos do exercício (e.g., apoptose de algumas células) podem estimular a mobilização de células estaminais hematopoiéticas da medula óssea e de células imunes senescentes dos tecidos periféricos para a circulação46.

Mas a resposta imunitária aguda ao exercício depende da duração e intensidade do mesmo. No âmbito da revisão efectuada por Nieman et. al.4, os autores diferenciaram exercício moderado e vigoroso, utilizando um limiar de intensidade de 60% do VO2 máximo e frequência cardíaca de reserva, e um limiar de duração de 60 minutos. O exercício agudo estimula o intercâmbio de células e componentes do sistema imunitário inato entre os tecidos linfóides e o sangue. Embora transitório, ocorre um efeito cumulativo ao longo do tempo, com melhor vigilância imunitária contra agentes patogénicos, células cancerígenas e uma diminuição da inflamação sistémica4. É por este motivo que tanto a saúde como a imunidade constroem-se todos os dias e não com shots de imunidade, com exercício pouco consistente ou com programas de transformação corporal de curto prazo.

Durante exercícios aeróbios de intensidade moderada e vigorosa em períodos de duração inferior a 60 minutos, a actividade protectora dos macrófagos teciduais ocorre paralelamente a uma recirculação aprimorada de imunoglobulinas, citocinas anti-inflamatórias, neutrófilos, células NK, células T citotóxicas e células B imaturas, que são essenciais na melhoria da saúde imunitária e na saúde metabólica. Estas sessões curtas de exercício de intensidade moderada mobilizam preferencialmente as células NK e as células T CD8+, que exibem alta citotoxicidade e vão atacar especificamente as células infectadas. Ao longo do tempo esta imunovigilância vai aumentando e, naturalmente, o potencial terapêutico do exercício também.

Muitos estudos sustentam que altas cargas de trabalho, competições e o stress fisiológico, metabólico e psicológico associados estão ligados à disfunção imunitária, à inflamação, ao stress oxidativo e ao dano muscular. De facto, vários biomarcadores da função imunitária podem ficar alterados durante várias horas a dias durante a fase de recuperação, mas isto acontece especialmente no caso dos indivíduos que fazem exercício prolongado e intenso, como por exemplo maratonas. A ligação entre exercício intenso e prolongado e o aumento do risco de doença já tem sido estudada desde os anos 80 / início dos anos 90. Os primeiros estudos epidemiológicos indicaram que os atletas envolvidos em eventos de maratona, ultramaratona e/ou de intensidades muito elevadas estavam em risco aumentado de infecções do trato respiratório superior.

Na realidade, quando analisamos os estudos realizados neste âmbito (relação entre exercício vigoroso e doença), verificamos que a maioria foram realizados com atletas de endurance (maratonistas, ultramaratonistas, triatletas, nadadores, esquiadores) e com atletas de elite, indivíduos que são submetidos a cargas de trabalho e a níveis de stress bastante diferentes de um atleta recreativo. O custo de se tornar um atleta de elite será sempre a saúde e como tal não podemos comparar laranjas com maçãs. Embora Campbell et. al.47 tenham desafiado o significado clínico e a ligação entre esforço intenso e disfunção imunitária transiente (uma questão que irá ser explorada mais abaixo), a maioria dos investigadores na área da imunologia do exercício apoia a posição que o sistema imunitário reflecte a magnitude do stress fisiológico imposto ao seu praticante. Mas atenção, isto não significa que a intensidade não possa ser elevada, isto significa é que a intensidade e outras variáveis do treino precisam de ser geridas de forma criteriosa.

Influências clínicas do exercício crónico nas infecções respiratórias

Cada período de actividade física moderada promove melhorias transientes na imunovigilância e, quando repetida regularmente, confere múltiplos benefícios à saúde, incluindo menor incidência de doenças respiratórias e inflamação. Os ensaios clínicos randomizados (8 semanas a 1 ano de duração)21,49-53 são consistentes na demonstração que os indivíduos que participam em programas de exercício moderado ou meditação52,53, experimentam menor incidência e duração de infecções do trato respiratório superior. A magnitude da redução destes sintomas com a realização de exercícios moderados quase diários é geralmente de 40% a 50%, excedendo os níveis relatados para a maioria dos medicamentos e suplementos.

Neste estudo efectuado por Nieman et. al.48, foram seguidos durante 12 semanas um grupo de 1002 adultos (18-85 anos; 60% mulheres e 40% homens), metade durante o inverno e a outra metade durante o outono, com a finalidade de monitorizar os sintomas de infecções do trato respiratório superior. Os resultados indicaram que o número de dias com infecções respiratórias foi 43% menor em indivíduos envolvidos numa média de cinco ou mais dias por semana de exercício aeróbio (20 minutos ou mais) em comparação com os indivíduos sedentários (≤ 1 dia / semana) e 46% menor para aqueles que estavam em melhor forma física.

Adicionalmente, conforme referido na secção “efeitos do exercício na imunosenescência”, há também uma melhoria na resposta de anticorpos à imunização contra o vírus da gripe em idosos que incorrem em programas regulares de exercício físico20.

O mito da supressão imunitária induzida pelo exercício

Num artigo de revisão publicado há cerca de dois anos atrás, Campbell et. al47, colocaram algumas questões relevantes, que devem merecer a nossa atenção. Os estudos que indicaram um maior número de infecções do trato respiratório superior decorrentes da “actividade física”, além de terem sido auto-reportadas (i.e., não foram efectivamente medidas através de análises laboratoriais), foram realizados em maratonistas e ultramaratonistas, sugerindo que essas infecções têm maior probabilidade de acontecer quando a duração e a intensidade do exercício são muito elevadas. Por outro lado, é preciso ter presente que essas infecções poderão também ser o resultado de muitas outras causas, algumas mais directamente associadas com essas práticas desportivas (cargas de trabalho muito elevadas, alergia, asma, inflamação não específica das mucosas, hiperventilação própria do exercício, exposição a temperaturas mais frias) e outras de carácter mais geral mas não menos importantes (maior stress psicológico, ansiedade, deficiências nutricionais, exposição a grandes aglomerados populacionais, fadiga, sono inadequado, viagens e adaptação a novos fusos horários, desidratação). Isto significa que o sistema imunitário poderá já estar em maior risco antes de iniciar o exercício. Assim, da mesma forma que existe evidência (com as devidas limitações) a confirmar que o exercício pode aumentar o risco de infecção, também existem vários estudos epidemiológicos a indicar que o exercício pode reduzir o risco de infecção, inclusivamente em atletas de elite, que estão sujeitos a elevadas cargas de trabalho.

Outro pilar da imunologia do exercício que recebeu considerável atenção nas últimas três décadas é a avaliação das alterações induzidas pelo exercício na imunidade das mucosas, principalmente através da medição dos níveis de anticorpos da imunoglobulina A (IgA) na saliva. A função principal da IgA é prevenir a entrada de organismos invasores na circulação e como tal a sua concentração aumentada ou diminuída poderá revelar uma imunidade mais forte ou mais fraca, respectivamente. Mais uma vez, os estudos aqui estão divididos e os autores apontam várias limitações que podem deturpar a secrecção de IgA: os níveis absolutos de IgA relatados não controlaram adequadamente a quantidade de saliva produzida; o estado da saúde oral é raramente avaliado; ritmo circadiano; stress psicológico; género; etnia, doença; medicamentos; tabaco e fase do ciclo menstrual. Pelo que é arriscado dizer-se que quaisquer alterações subtis na IgA salivar após o exercício reflectem a supressão imunitária e um risco aumentado de infecções oportunistas.

Já constatamos que o sistema imunitário é estimulado durante o exercício mas nas horas após o exercício, geralmente é observado que a frequência e capacidade funcional dos linfócitos do sangue periférico diminui para níveis inferiores ao pré-exercício, levando alguns autores a propor que o exercício induz uma janela de imunosupressão, fenómeno designado de “janela aberta”. Mas em vez de suprimir a competência imune, um ponto de vista mais actual é que essa linfopenia aguda e transitória 1 a 2h após o exercício é benéfica para a vigilância e regulação imunitária. De facto, no que parece ser uma resposta altamente especializada e sistemática, tem sido proposto que o exercício vai, por via da estimulação adrenérgica e libertação de adrenalina, mobilizar as células imunitárias para a circulação e depois redistribuir essas mesmas células para os tecidos periféricos (i.e., superfícies mucosas como pulmões, intestino, pele) para conduzir a vigilância imunológica e providenciar feedback à medula óssea para iniciar a produção de novas células imunitárias. Estas células imunitárias são recrutadas do baço, dos nódulos linfáticos, do intestino e de células imobilizadas ao longo das paredes vasculares. Esta redistribuição das células imunitárias (em particular das células NK) é, na verdade, um dos mecanismos apontados para a redução dos tumores em pacientes com cancro54,55 (infelizmente esta forma de imunoterapia ainda não é levada a sério) e o seu aumento é proporcional à intensidade do exercício56.

Para haver adaptações significativas ao nível do treino é preciso que o mesmo seja progressivamente intenso. Intenso não significa necessariamente mais longo, significa intenso para o indivíduo que está a realizar o exercício. E para fazê-lo de forma responsável, é preciso atender ao seu historial clínico, à sua mobilidade articular e à sua capacidade de trabalho, ou seja, é preciso avaliar o indivíduo para poder compreender a sua tolerância. Um indivíduo que treina de forma consistente há muitos anos terá respostas diferentes ao nível do sistema imunitário quando comparado com um indivíduo sedentário ou pouco regular no exercício. Tal como qualquer intervenção cirúrgica, o exercício também precisa de ser bem administrado para ser eficaz.

Conclusão

Vivemos numa cultura de elevado sedentarismo em que não é necessário fazer qualquer tipo de esforço físico para sobreviver. As pessoas habituaram-se a não fazer nada do ponto de vista físico para sobreviver mas agora de repente parece que descobriram que podem e devem ser mais activas. A disseminação de exercícios sem critério e de aulas online gratuitas nestes últimos tempos tem sido própria da histeria que se vive num arraial. A falta de consciência de alguns profissionais, que certamente estão a tentar ajudar, também não tem ajudado. O que mais me preocupa nesta história toda é que na internet vale tudo e não há qualquer tipo de filtro. E devido a esta falta de cultura e literacia física colectiva, a maior parte das pessoas não tem educação suficiente para distinguir o bom do mau, nem o excelente do medíocre. Qualquer coisa serve, independentemente se tem qualidade ou não.

Para quem não sabe para onde vai qualquer caminho serve, disse o gato na célebre história de Alice no País das Maravilhas, em resposta à sua exclamação “eu não sei para onde quero ir!”. Esta questão do covid-19 veio confirmar que a atitude diária das pessoas rege-se mais pelo medo, que pelos seus objectivos e desejos. Os media sabem disso e exploram muito bem essa fragilidade das pessoas. O bombardeamento de informação sobre esta matéria tem sido estridente e hoje em dia é cada vez mais difícil distinguir a verdade da mera opinião de jornalistas e de pseudo-especialistas. O medo é o principal supressor do sistema imunitário, o cortisol e as hormonas do stress vão superar a energia necessária para combater a infecção. Esta é uma questão que decorre da nossa evolução enquanto espécie, se estivesse doente e tivesse que fugir de um animal que me queria fazer mal, eu iria canalizar toda a minha energia para esse efeito, ou seja, eu iria lutar com todas as minhas forças para combater esse animal. A situação do covid-19 veio confirmar também que temos uma população débil que investe muito pouco no desenvolvimento da sua saúde e imunidade. E quanto maior o número de comorbilidades, sinais e sintomas de perda de saúde, maior é o risco de adoecer e morrer.

Em relação ao exercício físico, e com base na revisão de literatura efectuada e na nossa experiência prática no acompanhamento de indivíduos imunossuprimidos, maioritariamente doentes oncológicos, há várias coisas que deve fazer para aumentar a sua imunidade e bem-estar geral. Aqui ficam as principais recomendações:

- Mantenha-se o mais activo possível e evite passar muito tempo seguido sentado. Passar muito tempo sentado é altamente nocivo! Tenha presente que o movimento sempre foi uma necessidade essencial à vida humana e afecta todos os sistemas e órgãos do corpo. O facto de hoje não ter problemas de saúde devido ao seu comportamento sedentário é apenas uma questão de tempo. (nota: manter-se activo no seu dia a dia não é igual a manter as suas articulações, a sua postura, a sua musculatura e a sua competência de movimento em bom estado. Para optimizar a sua função corporal e retirar maiores benefícios precisa de dedicar tempo à avaliação e ao tratamento da sua condição músculo-esquelética).

- Seja consistente na sua adesão ao exercício físico. Procure formas de exercício prazerosas, que lhe permita manter uma frequência semanal elevada (5-6x por semana, idealmente). A intensidade deverá naturalmente oscilar entre moderada e vigorosa. Há um efeito cumulativo na construção da imunidade. Os indivíduos que são mais consistentes ao nível da sua prática de exercício estruturado têm menor incidência de doenças, registam uma maior eficácia ao nível da vacinação e têm um sistema imunitário mais vigilante. A prática de meditação também tem mostrado resultados na prevenção de infecções respiratórias, e é importante na gestão do stress e na melhoria do bem-estar geral.

- Em função da sua condição, privilegie formas de exercício seguras que permitam realizar intensidades elevadas de curta duração (a evidência aponta como limiar 60 minutos de duração) ao invés de intensidades elevadas de longa duração. A lógica do “no pain, no gain” é simplesmente imbecil e só faz sentido se você não estiver preocupado com a sua saúde e longevidade. Os eventos de endurance de intensidade elevada poderão suprimir o sistema imunitário e aumentar o risco de doença e infecção do trato respiratório, especialmente se não tiver os cuidados adicionais na sua preparação. No que diz respeito à intensidade, podemos compreendê-la de duas formas: 1) intensidade ao nível da activação neuromuscular / contracção muscular (com a utilização de vários protocolos de treino de força) e 2) intensidade ao nível da capacidade dos sistemas energéticos (com a utilização de vários protocolos de treino de métodos intervalados e/ou de métodos contínuos). Intensidades elevadas, se pensarmos numa escala de 1 a 10, em que 1 é pouco intenso e 10 muito intenso, referimo-nos a uma percepção de esforço de oito para cima.